How the Northern European Forest Commons Can Inform Modern Heathen Practice in Canada

This is part 4 of my blog series on the Forest Commons of Northern Europe. The previous section was on how the Enclosure Movement affected colonization in Canada and elsewhere and how Canadians can ally with Indigenous peoples going forward. Previously we also talked about what the Forest Commons were and their History up to modern day. If you haven’t read those posts yet, you may want to loop back to them.

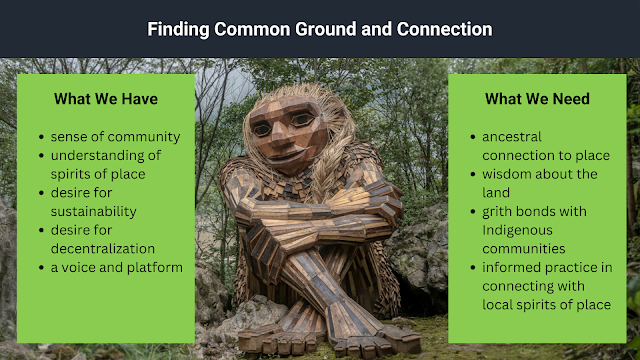

This post will be about modern Heathenry in Canada and building grith with Indigenous Communities. In this post we will examine stories from Indigenous peoples of North America as well as Heathen stories, and attempt to create common ground. We will discuss:

Spirits of Place

7 Generations philosophy and being good ancestors

The importance of community

Sacred Trees

Ancestry and connection to land

Gifting practices

Ways to move forward

An important part of Heathenry is the veneration of Spirits of Place. Understand this to be spirits who would aid humans, not malevolent spirits. Heathens usually believe that there are spirits all around us in rocks, trees, and landforms. These spirits should be respected and honoured when we are on the land that they call home. We honour these spirits through the gifting cycle, which is giving gifts in hopes that these spirits will see us favourably and treat us fairly.

It seems to me that there is a very close parallel between Heathen gifting and reciprocity with Spirits of Place and the Indigenous ideology surrounding the Honourable Harvest. This is the concept of approaching the spirit of an animal or plant before taking its life or some of its vitality to sustain your own. It is about making sure that there is enough of something before you take, to ensure sustainability, and also about asking permission from that spirit.

It is important as Canadian Heathens to think about the implications of our actions. We should learn about Honourable Harvest practices. We should also think about what gifts we give to the Spirits of Place and tailor them to our landscape. In Europe gifts were often things like milk or alcohol, but we need to be mindful of the feelings of the beings around us. These gifts may not be well received here. We may want to instead offer tobacco or cornmeal, or something that will not harm the local environment such as water or herbal tea.

I have also heard that some Indigenous groups do not believe it is wise to recognize the Spirits of a Place because that would draw attention to you that may not be wise. It is important to learn about the place where you live, its history, and the customs of the Indigenous peoples who live there to help determine the best way to relate to the Spirits of Place.

Long ago the world was covered in water. Above the world lived the Sky Chief and his daughter, who was pregnant. In the lands of the Sky Chief there was a great tree, whose seeds were medicines. At the base of the tree was a hole in the clouds looking down on the world below. One day the Sky Daughter went to the base of the tree to peer down at the world below, but she lost her balance and fell through. She tried to grasp a branch so she did not fall, but instead only grasped a handful of seeds.Below in the water there were animals who saw the Sky Daughter fall and they knew she could not live in the water like them. They rushed to her aid.“Put her on my back.” said Turtle and the other animals did. But they knew that she could not live like that and needed ground.One of them said, “There is soil far below the water if we could get to it.”Each one tried, and each could not swim deep enough to reach it. Finally Muskrat said, “I will try.”The other animals laughed because he was so small, but Muskrat dove.And he was gone so long that the other animals began to worry he would not resurface.Eventually he did but he collapsed and the other animals placed him on Turtle’s back along with the Sky Daughter. It was a while before one of them noticed that Muskrat’s hand was clenched shut. They pried it open to find it was full of soil.They spread the thin layer of soil on Turtle’s back, praising Muskrat for his bravery. In the soil the Sky Daughter planted all the seeds. They grew into all of the plants that we now know. All of the plants we use for food and medicines, and the four sacred herbs. Soon the Sky Daughter gave birth to twins and from them came all people, and some of the animals joined her on Turtle’s back as well. If you look at a map of North America you will see it is shaped like a Turtle.

Understanding Ancestry and Connection to the Land

For many Indigenous peoples home is not a building, but a sense of place, a connection to the land and the different beings that live there. The connection to the land is measured in the presence of the ancestors' bones beneath our feet. Wisdom of the land and how to survive is passed down from generation to generation. The way of living for Indigenous people reflects their closeness to the land and preserving it for future generations.

When I was in university I took a course in Canadian Poetry. At the time there was a resident poet at the university who was an Indigenous woman, and she spoke in class one day. We were reading a poem by Margaret Atwood called “Death of a Young Son by Drowning.”

He, who navigated with successthe dangerous river of his own birthonce more set forthon a voyage of discoveryinto the land I floated onbut could not touch to claim.[...]After the long trip I was tired of waves.My foot hit rock. The dreamed sailscollapsed, ragged.I planted him in this countrylike a flag.

What the resident poet then said stuck with me, “Indigenous people see white people as pale ghosts drifting across the landscape. They cannot connect without the bones of the ancestors beneath their feet.”

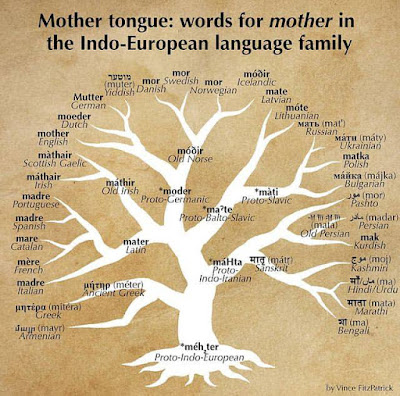

It was these words that informed my own practice as a Heathen, when I found myself moving halfway across the country and finding it difficult to connect with the land around my new city. I was lucky enough to have had family who lived here previously. I went to my grandfather’s grave and I asked him to help me connect with the land. After I asked, the wind picked up. Since then it has been smooth sailing. Our ancestors connect us to the land. In the Havamal it says, “A rootless tree cannot be trusted.” Don’t be a rootless tree. That is the challenge of being a Heathen in Canada. Not all of us have ancestors beneath our feet to guide us. Some of us have to be the ancestor. And that I think is why us as non-Indigenous Canadians, and often us as Canadian Heathens, are interested in lineage. It isn’t all about blood ancestry. As Mathias Nordvig said in his podcast, The Sacred Flame, “You are a nobody.” The idea of blood ancestry was elitism among the nobility of Europe. Most of us descended from the common people.

We are not special. Our blood lineage doesn’t make us special. Our race doesn’t make us special. All that lineage affords us is an understanding of where we came from. It keeps us from being rootless trees. But if we think about Yggdrasil we must remember that Nidhoggr lived among the roots feasting on the things that decayed. That is the natural order. We cannot preserve the roots that are damaged and corrupted and hope to maintain a healthy tree. Nidhoggr is necessary. We must tend to the flame, not worship the ashes.

Take what is necessary from our shared history in order to build a better future, and be the best ancestors we can be.

Gifting Practices

For Heathens the ideas of gifting and reciprocity are how we relate to the world around us. I talked briefly about building relations with Spirits of Place through the gifting cycle, but we do similarly when relating to our ancestors and the Gods. More importantly to this narrative, we also use the gifting cycle to build relationships with people. In Heathenry we say “a gift for a gift” and what we mean is that when we gift something to someone they are more likely to view us favourably and build a relationship with us. Gifts are given back and forth to maintain friendships. Not all gifts are tangible things, but rather things that the other person sees as valuable. This could be helping someone move or taking them out for lunch or helping them edit a school paper or whatever. This is the basis for all relationships in Heathenry.

In Indigenous practices gifting is also important. The Potlatch among Northwest Coastal communities was a gifting ceremony that helped to cement status. Another example of gifting is the Cree idea of the host giving a blanket to a guest. The idea was that if you got stranded on the way home, at least you would have a blanket.

In many ways Indigenous ideas on gifting are similar to gifting among the historic Heathens of Northern Europe, where the host would give gifts to the guests to cement status and gain favour with them.

Why is gifting important to this conversation? We need to develop relationships with Indigenous peoples based in trust and reciprocity. We need to show through actions, not just words, that we are allies, and we need to open the doors to communication between our communities. In Heathenry, we call this “grith” which is a relationship of reciprocity between communities or members of separate communities, whereas we use “frith” to describe a similar relationship within our own community.

.png)